Features

Biomimicry versus Biophilia: What’s the Difference?

Allison Bernett

Share

Learn more about our work and services in biophilia and bioinspired innovation by emailing us at [email protected]. Follow the conversation on twitter: @TerrapinBG

You know you’ve crossed a special threshold in sustainable design when one of your biggest pet peeves is people confusing biophilia and biomimicry. I’m going to put my greeny geekiness on full display by dedicating a whole blog post to straightening out this common confusion.

It’s easy to mix up these two terms — biomimicry and biophilia are similar in many ways. They sound similar, they were both born out of the environmental movement, and they both relate to nature. However, they define different concepts with different aims. Understanding how they differ and what issues they solve is key to unlocking the breadth of solutions nature has to offer — from sustainable, innovative designs to improved human health and wellbeing.

So What’s the Difference?

In a nutshell, biomimicry is the “mimicry,” or more accurately, the emulation of life’s engineering. In contrast, biophilia describes humans’ connection with nature and biophilic design is replicating experiences of nature in design to reinforce that connection. Biomimicry is an innovation method to achieve better performance; biophilic design is an evidence-based design method to improve health and wellbeing. Biomimicry is more heavily used in technology and product development circles; biophilia applies more directly to interior design, architecture, and urban design.

Essentially, these two concepts draw upon nature in different ways. Biomimicry recognizes the innovation potential of life’s tested-and-true “technologies.” Biophilia recognizes the health benefits of mankind’s biological connectedness with nature. Together, they show the diversity of inspiration we can derive from nature. Still confused? Let’s dig a little deeper into each concept…

Biomimicry

noun | bio·mim·ic·ry | \¦bī-ō-¦mi-mi-krē\

Biomimicry is the conscious emulation of natural forms, patterns, and processes to solve technological challenges. It leverages nearly 4 billion years of nature’s evolutionary problem-solving to create high-performance and generally more sustainable designs and technologies. It is, in essence, an alternative method to innovating where the first step is to understand how nature overcomes similar challenges to the design or engineering challenge encountered and then to apply that knowledge.

Corals use dissolved CO2 in the ocean to build their skeletons. Blue Planet’s technology mimics this process to create carbon positive materials. Image copyright USFWS Pacific Region/Flickr.

Biomimicry is one of several terms — along with biomorphism and bioutilization — that falls under the umbrella of what Terrapin calls “bioinspired innovation” (read one of my earlier posts distinguishing these terms). Biomimicry and other forms of bioinspired innovation can be used to tackle challenges at many scales and across industries (see the interactive infographic in Tapping into Nature to explore over 100 bioinspired technologies and their associated industries).

One of my favorite examples of biomimicry is Blue Planet’s carbon-positive cement and building materials. Blue Planet’s technology mimics corals’ ability to use dissolved CO2 in ocean water to build their hard calcium carbonate skeletons, a process called biomineralization. Blue Planet’s process starts by extracting CO2 from flue gas (the stream emitted from coal plants and other combustion sources) and combines it with a source of calcium to create cement, aggregate, pigments, and roofing tiles. This low-energy chemical process sequesters carbon in a durable form rather than releasing it into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas. By emulating how natural organisms use CO2 as a resource, Blue Planet has created a unique carbon capture solution.

Biophilia

noun | bio·phil·ia | \ˌbī-ō-ˈfi-lē-ə, -ˈfēl-yə\

Biophilia, although most commonly known as the title of a Björk album, is garnering a lot of interest from the design community. Biophilia, which translates to “love of life,” signifies humans’ innate biological and emotional need to connect with nature. Biophilic design endeavors to forge this connection by leveraging or inserting instances of nature, natural patterns, or spatial conditions into the built environment.

COOKFOX Architects’ office in New York overlooks a green roof and the city skyline. Especially with these features, it is a great example of biophilic design. Image copyright COOKFOX Architects.

Biophilic design sounds great to nature-lovers like myself who crave hiking through natural landscapes or visiting the local aquarium. But what’s the significance of biophilia to the rest of the population who would prefer a spa weekend to a camping trip? Research in environmental psychology and neuroscience continues to demonstrate that certain elements and conditions in nature have significant benefits to our health and wellbeing. Biophilic elements have been shown to reduce stress, improve cognitive performance, and support positive emotions and mood. Biophilic design applies the science in order to create healthful spaces in a variety of environments, from schools and workplaces to hotels and urban streetscapes.

Since it’s difficult and unnecessary to plant a forest in your office, Terrapin instead works with the 14 patterns of biophilic design to create targeted instances of nature in spaces. Each pattern refers to a specific natural element that has been shown to have beneficial health effects. Some patterns are intuitive, like Visual Connection with Nature, which can be achieved by having indoor plants or water features. Others are less obvious, like Prospect, which refers to spatial conditions where one can survey a space or has a view across an expanse. The COOKFOX office is a great example of a space that demonstrates both patterns.

Some Similarities

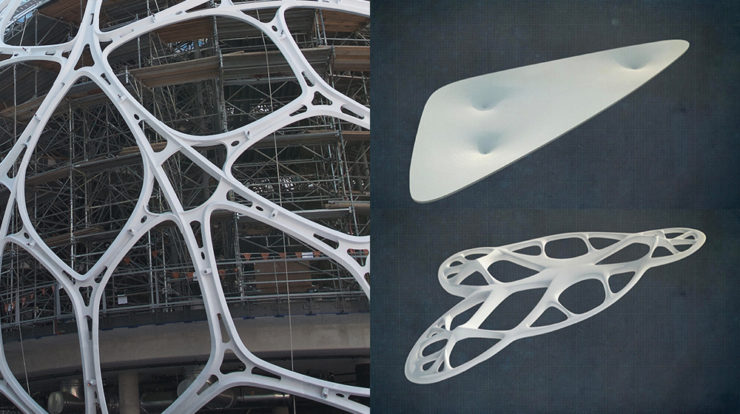

The Landesgartenschau Exhibition Hall is a good example of both biomimicry and biophilia. Image copyright Roland Halbe.

Now, some of you familiar with these fields may argue that the difference between biomimicry and biophilia is not always clear-cut. Biomimicry and biophilia do overlap. Most commonly, biomimicry and biophilic design come together in biomorphism, or the mimicry of natural forms. Take for instance the striking Landesgartenschau Exhibition Hall by Achim Menges at the ICD Universität Stuttgart, which derives its lightweight form and paneled construction from the sea urchin’s shell morphology of interlocking bony plates. It is certainly biomimetic since its structural characteristics were inspired by the sea urchin. It is also biophilic since it possesses characteristics of Pattern 8: Biomorphic Forms & Patterns.

However, not all biomorphic designs are necessarily biomimetic or biophilic. If the design does not adhere to biological principles that imbue it with superior performance, we do not consider it true biomimicry. Likewise, not all biomorphic forms are biophilic. If a biomorphic form mimics creatures like snakes or spiders that are perceived by humans as dangerous, they can elicit a fear response — a reaction termed “biophobia.” Such designs do not support positive health benefits, and therefore we do not consider them biophilic. In ambiguous cases, what is considered biomimicry or biophilia can become a matter of opinion. Ultimately, what truly matters is whether the design, technology, or product achieves the desired outcomes, such as high-performance, sustainability, or positive effects on health and wellbeing. Using these terms of biomimicry and biophilia gives us a common language and accepted methodologies that consistently yield effective designs.

Rooted in the Same Philosophy

In addition to some similar outcomes, biophilia and biomimicry are also both founded upon a deep appreciation of nature. Each concept recognizes that nature provides us with an untapped source of solutions to our most dire issues. Biomimetic technologies like Blue Planet provide solutions to reverse climate change. Biophilic design counters the adverse health effects of urban environments, a critical issue in light of rapid urbanization.

More deeply, these concepts represent a collective reaction against the ill effects of the industrial age and our perceived dominion over nature. Biomimicry, biophilia, and other offshoots of the sustainability and green building movement herald a paradigm shift in our relationship with nature. We have begun to realize that our current mode of living is unsustainable and that we deeply depend on the health of natural ecosystems and the planet to survive and thrive. The early successes of biomimicry and biophilia demonstrate how working with nature is the next logical step toward establishing restorative systems that help us create a more prosperous future.

QUIZ: Do You Know the Difference Between Biophilia and Biomimicry?

Do you think you know the difference between biophilia and biomimicry? Put your knowledge to the test by taking our short quiz below:

Directions: Study each example described below and select whether you think it is an example of biomimicry, biophilia, both, or neither.

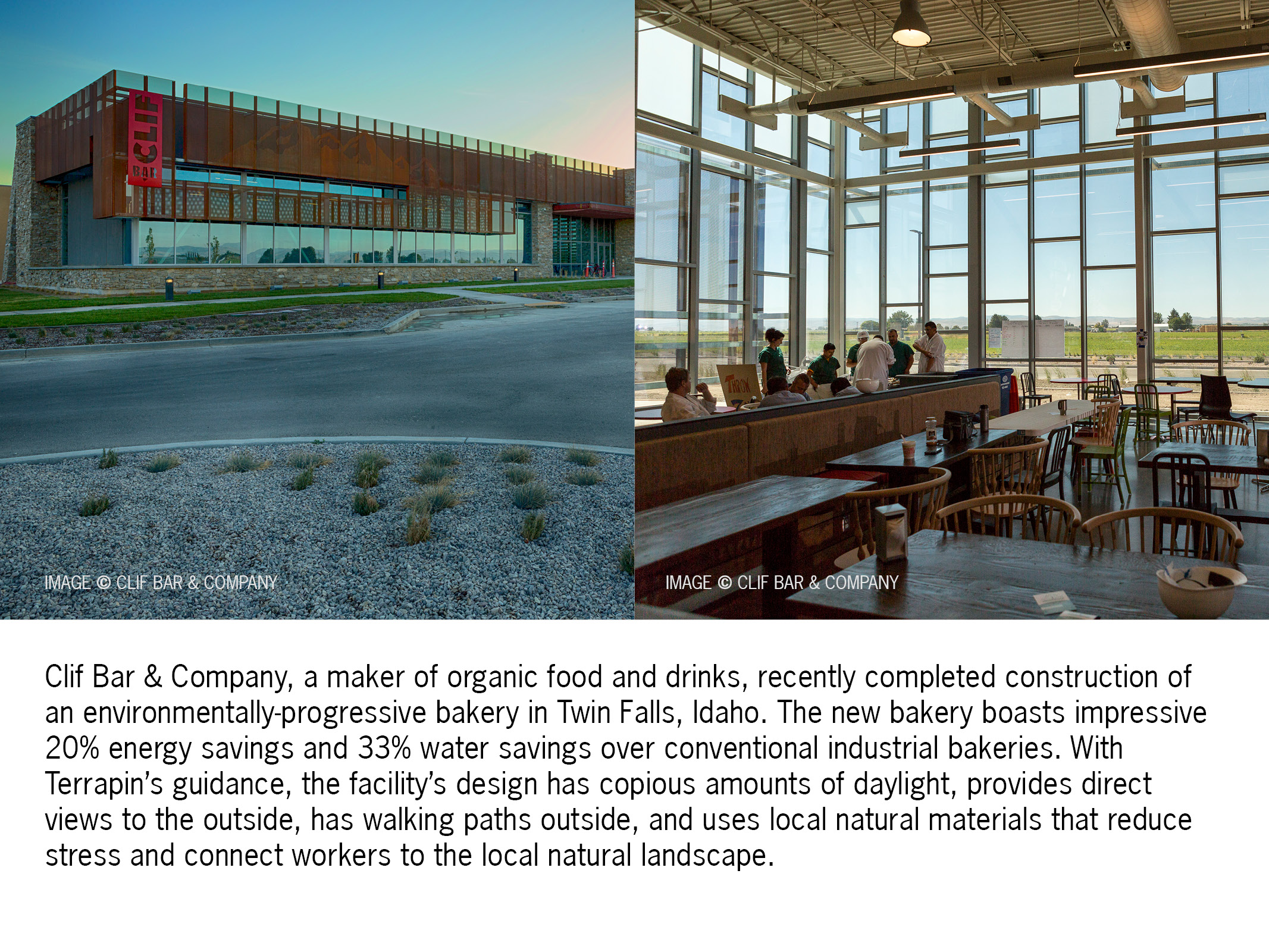

Clif Bar Bakery

Clif Bar & Company

Clif Bar & CompanyThe Clif Bar Bakery is an excellent example of several biophilic design patterns that connect occupants to the natural environment, such as Dynamic and Diffuse Light through daylighting, Visual Connection to Nature through views to the outdoors, and Material Connection with Nature through the use of local natural materials. It is not biomimetic because it doesn’t emulate any natural form, function, or process to solve a challenge.

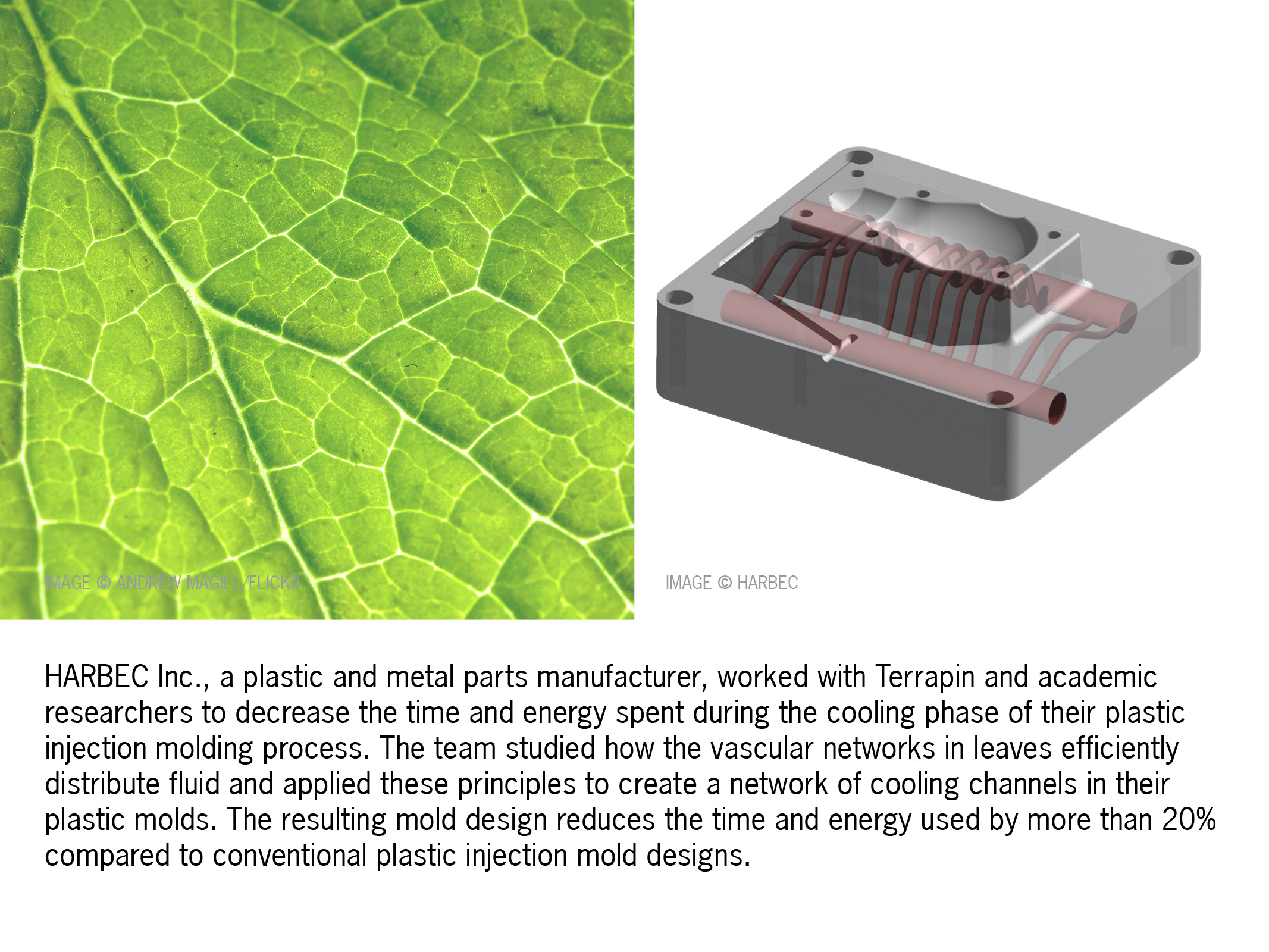

HARBEC Plastic Injection Molds

HARBEC

HARBECHARBEC’s plastic injection mold design was informed by the leaf vein arrangement and function, a clear emulation of a natural process to solve an engineering challenge. It is not biophilic because it does not connect humans to nature.

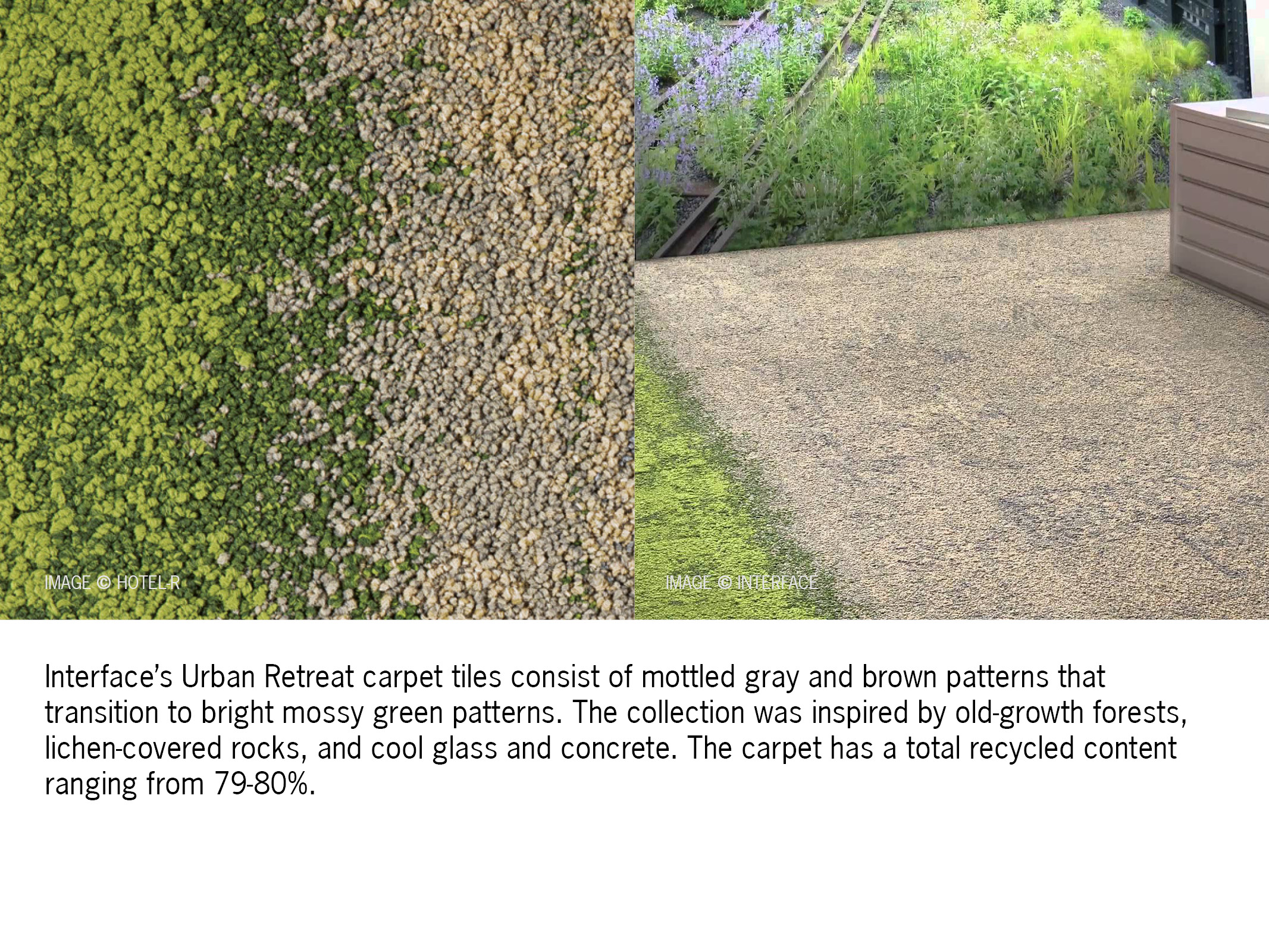

Interface Urban Retreat Carpet

This carpet uses patterns, forms, and colors similar to those seen in a forest, which is in line with the biophilic design patterns of Biomorphic Forms & Patterns and Material Connection with Nature. Although it was inspired by natural examples, these carpet is not biomimetic because its design does not emulate the function of a natural example for improved performance. However, if you are familiar with the backstory of Interface's carpet tiles, this is not a clear-cut example. The randomized patterns and mergeable dyelots in their carpet tiles were inspired by the aesthetically coherent but non-repeating patterns found in the forest floor, making each carpet tile pattern unique and allowing the carpet tiles to be installed in any orientation. This drastically reduces the installation time and manufacturing waste (since carpet tiles are not being discarded for having errors in the patterning). Interface came to this innovative idea through a biomimetic process -- by studying nature's patterns and applying lessons learned.

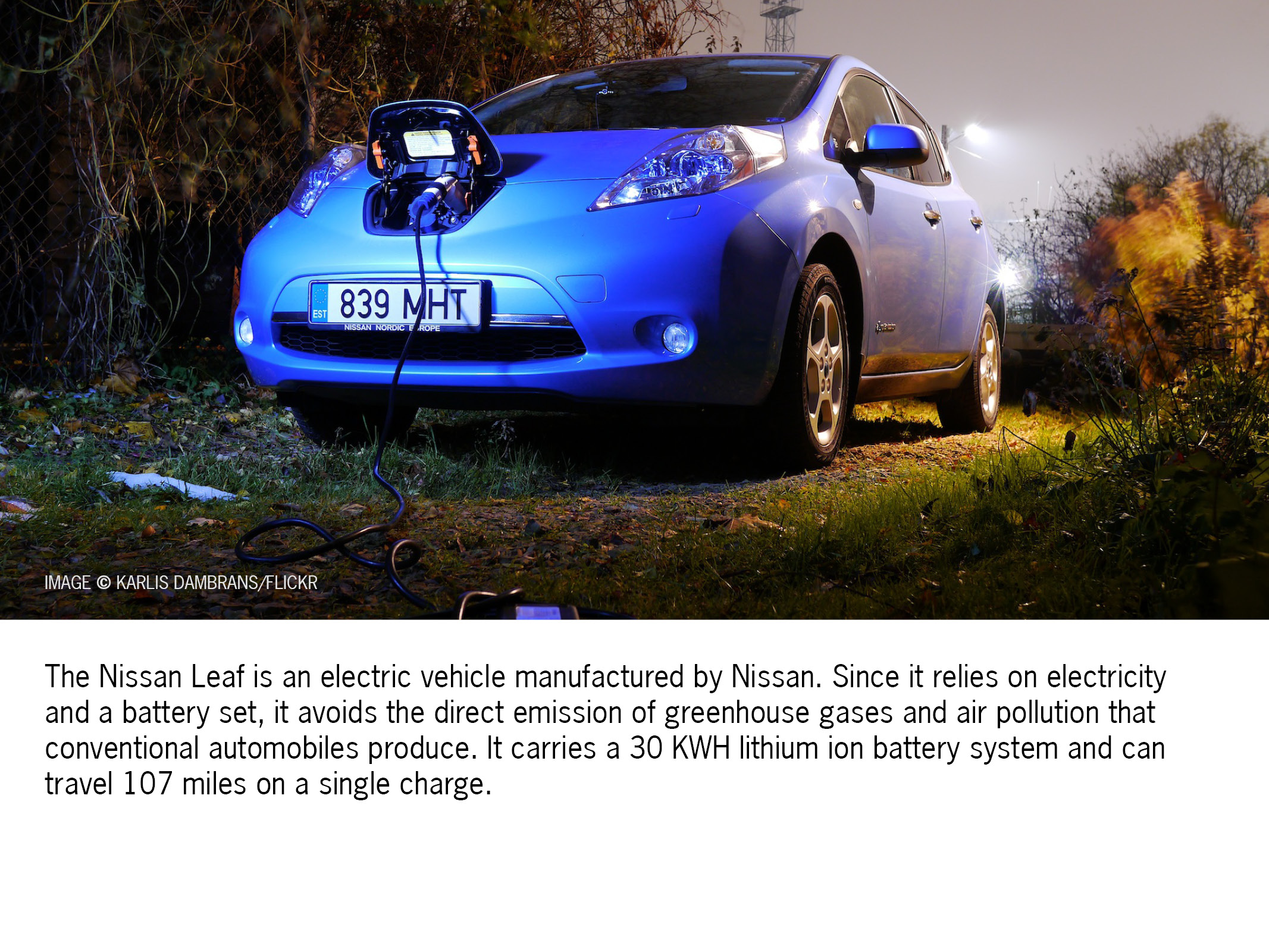

Nissan Leaf

Hopefully, this one was easier. The Nissan Leaf represents a great technology that, as electric grids transition to renewables, provides a sustainable alternative to conventional gasoline-powered vehicles. However, it does not emulate a natural form, pattern, or process to overcome a technological challenge nor does it connect occupants to nature in any large way, so it is not an example of biomimicry or biophilia.

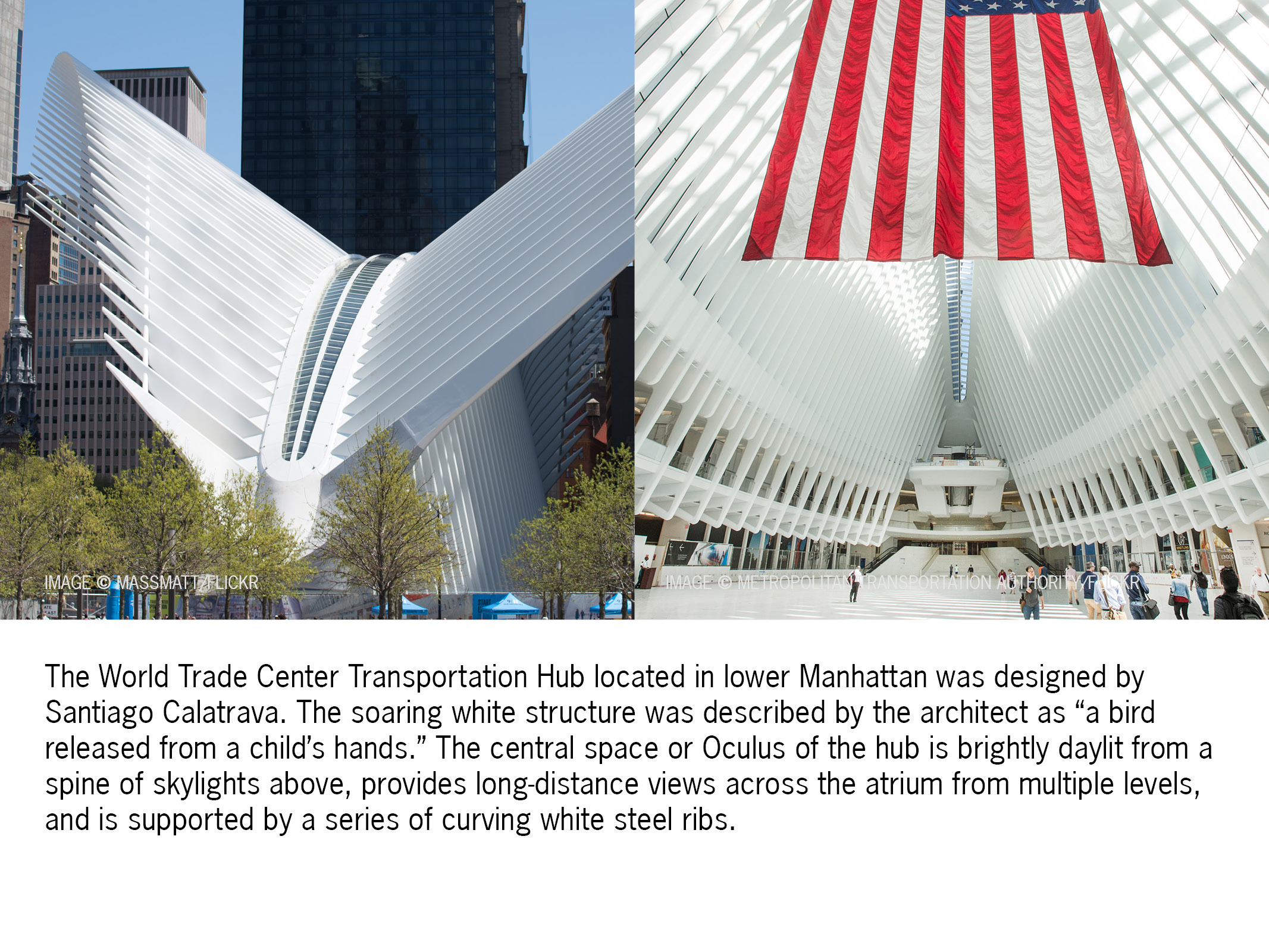

World Trade Center Transportation Hub

This one is a little tricky. The striking form of the building was intentionally biomorphic, recalling skeletal structures and bird wings. This combined with biophilic patterns like Dynamic & Diffuse Light, Complexity & Order, and Prospect abstractly connects occupants to nature, making it a clear example of biophilia. However, its biomorphic form, though inspired by natural forms, does not overcome a technological challenge resulting in higher performance -- in essence, it’s not a functional biomorphic structure and therefore not biomimetic.

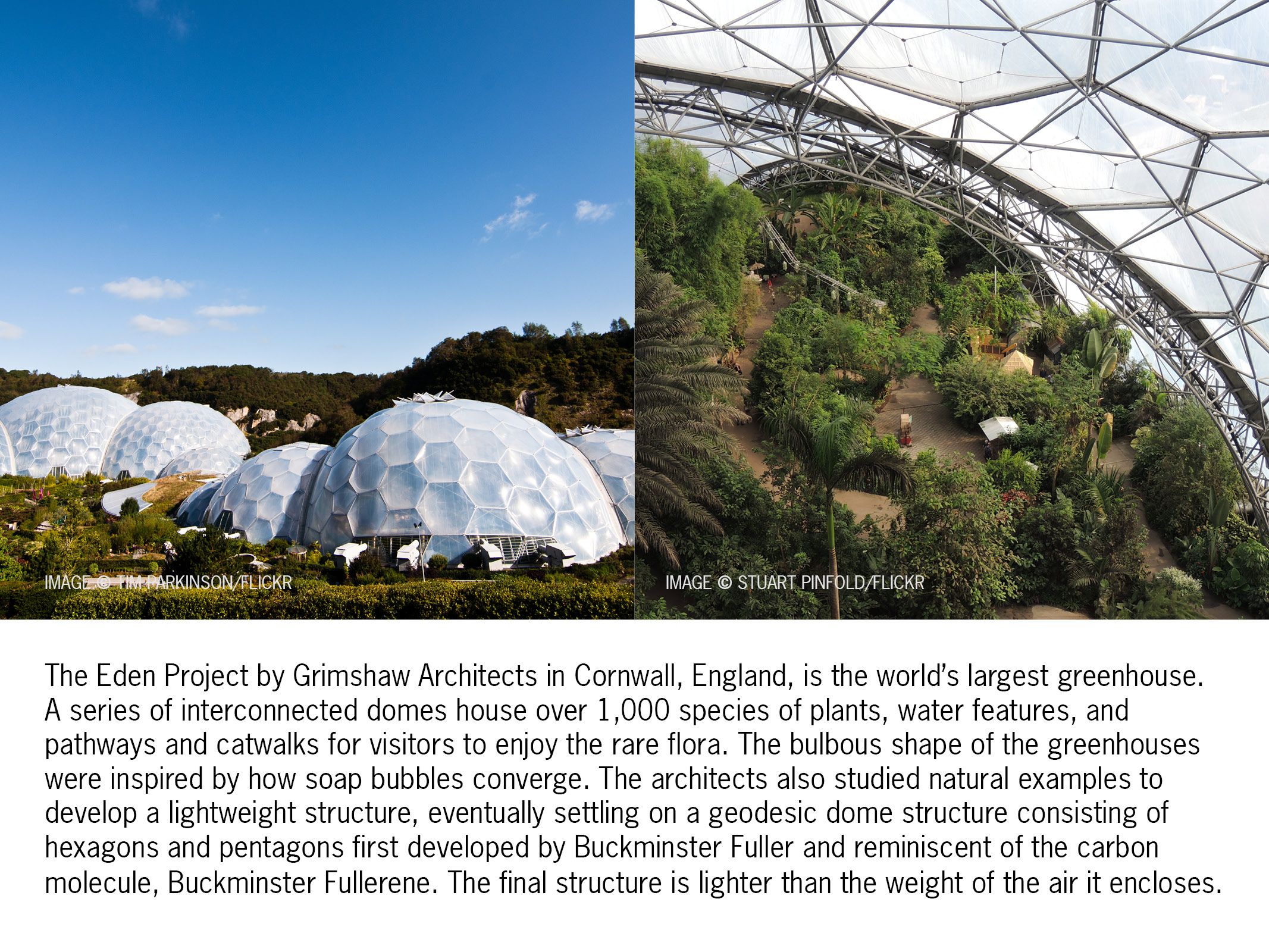

Eden Project

This is another tricky example. The Eden Project is most certainly biophilic, offering visitors a rare chance to experience a rainforest biome and providing Prospect views and Risk/Peril with the catwalks. It is also a good example of biomimicry because the architects emulated examples from nature to develop a remarkably lightweight structure that outperforms conventional methods and meets the challenging needs of this unique project.

Share your Results :

Sources:

- “2017 Nissan Leaf,” Nissan https://www.nissanusa.com/electric-cars/leaf/

- Clif Bar Project Profile, Terrapin Bright Green, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/blog/2016/09/clif-bar-biophilic-design-review/

- “Clif Bar Celebrates Opening of Its One of-a-kind Sustainable Bakery,” Clif Bar, http://www.clifbar.com/press-room/press-releases/clif-bar-celebrates-opening-of-its-one-of-a-kind-sustainable-baker

- Eden Project http://www.edenproject.com

- HARBEC Bioinspired Innovation Case Study, Terrapin Bright Green, https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/bioinspired-innovation-case-studies/

- Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry in Architecture, 2011, London: RIBA Publishing.

- “World Trade Center Transportation Hub / Santiago Calatrava” 21 Mar 2016. ArchDaily. Accessed 14 Feb 2017. http://www.archdaily.com/783965/world-trade-center-transportation-hub-santiago-calatrava/

*Feature images copyright Larry Miller/Flickr and PAX Scientific.

**Header images copyright Frank Fujimoto/Flickr and Aarhus School of Architecture.

Allison Bernett

Allison Bernett is an associate project manager and the public relations coordinator for Terrapin Bright Green. She graduated summa cum laude from Washington University in St. Louis with a double major in architecture and biology. Allison’s interests focus on architecture, sustainability, and bioinspired innovation.

Topics

- Environmental Values

- Speaking

- LEED

- Terrapin Team

- Phoebe

- Community Development

- Greenbuild

- Technology

- Biophilic Design Interactive

- Catie Ryan

- Spanish

- Hebrew

- French

- Portuguese

- Publications

- Occupant Comfort

- Materials Science

- Conference

- Psychoacoustics

- Education

- Workshop

- Mass Timber

- Transit

- Carbon Strategy

- connection with natural materials

- interior design

- inspirational hero

- biophilia

- economics of biophilia

- Sustainability

- wood

- case studies

- Systems Integration

- Biophilic Design

- Commercial

- Net Zero

- Resorts & Hospitality

- Energy Utilization

- Water Management

- Corporations and Institutions

- Institutional

- Ecosystem Science

- Green Guidelines

- Profitability

- Climate Resiliency

- Health & Wellbeing

- Indoor Environmental Quality

- Building Performance

- Bioinspired Innovation

- Biodiversity

- Residential

- Master Planning

- Architects and Designers

- Developers and Building Owners

- Governments and NGOs

- Urban Design

- Product Development

- Original Research

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Ecology

- Resource Management

- Sustainability Plans

- Health Care

- Carbon Neutrality