Contributions

The Multi-Sensory Experience of Design

Catie Ryan

Share

Learn more about our biophilic design work and services by emailing us at [email protected] and reading our reports, 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design and The Economics of Biophilia. Follow the conversation on twitter: @TerrapinBG | #14Patterns.

* This feature is a re-post from Catie’s on-going series for Human Spaces, powered by Interface, outlining each of the 14 patterns of biophilic design. For a more in-depth look at this pattern and others, see the publication “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design“.

Imagine a time when you’ve experienced complete silence in the forest. I bet you can’t. Only when there is impending danger do birds stop singing and scavenging creatures take pause. For urbanites, complete silence is also rare and unnatural. Sensory deprivation can be unsettling and sometimes even disconcerting, yet the power of our non-visual senses — sound, smell, touch, taste — is typically undervalued and often forgotten in the design experience. Consider the smell of impending snowfall, the burgeoning of balsam fir in the springtime, the feel of smooth cool river stones, and the crispness of autumn on your breath. Positive non-visual experiences, especially natural ones, can provide potent stimulation, giving biophilic designers a significant opportunity.

Pattern 2: Non-Visual Connection with Nature

While the benefits of a Visual Connection with Nature (pattern 1) are great, to only see nature is not to experience it. As the second biophilic design pattern, “Non-Visual Connection with Nature” aims to engender a deliberate and positive reference to nature, living systems or natural processes through greater access to auditory, haptic, olfactory, or gustatory stimuli. These sensory experiences can enhance the user experience through practical applications, unique unto themselves or, better yet, in combination with each other or with associated visual stimuli.

Interventions that focus on the visual connection can integrate other sensory stimuli for a more enhanced user experience.The Non-Visual Connection, like the other patterns, arose from evidence of its health benefits. Auditory (sound), olfactory (smell), haptic (touch) and gustatory (taste) experiences of nature are shown to help reduce stress, support healthy respiratory function and improve perceived physical and mental health. But how can we know which design interventions, or combinations of patterns, create the best experience? How much is a good thing? When is enough… enough? These are all great questions! Researchers in Finland, Japan and elsewhere are trying to answer them. In the meantime, consider your own experiences in nature. Often there is one sensory experience that dominates, while the others enhance the pleasurability of it, and your desire to relax and wish to stay there all afternoon. There’s a reason nature makes us feel this way. Research has shown that tree-derived essential oils are associated with improved immune function, that the scents of lavender, chamomile, and sandalwood can have anxiety-reducing effects, and that the scents of peppermint, jasmine, and rosemary improve alertness and cognitive performance. We can imagine spaces in the built environment where incorporating scent with these benefits would be most suitable.

The textures and temperatures of rocks, grass and pet fur each provide a tactile or haptic connection with nature.

We can design these spaces with deliberate multi-sensory experiences either by providing access to real connections with nature or by designing and engineering simulated connections. Ornamental vegetation can be fragrant and even edible. Mechanical systems that cannot draw directly from outdoors can be scheduled to release periodic bursts of natural scents. Consider that in nature, we do not experience scent in concentrated doses, like with perfume or scented candles; the experience is usually ephemeral, momentary and sometimes only seasonal.

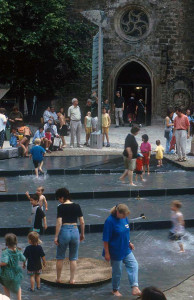

Just as sound is an inseparable facet of nature, acoustics is an age old problem for design. Perhaps we have too willfully brandished acoustics as a problem ‒ why don’t we make it an opportunity? It’s an artform in and of itself. We extol those spaces that achieve acoustical design excellence, such as Carnegie Hall by William Tuthill, and consciously avoid spaces with poor acoustics.Views to water fountains or bird activity can be supplemented by resonating their sounds inside the space from which they are viewed. Streaming water sounds can be an effective acoustic barrier with a calming effect. Providing a place to observe and even touch that water is more likely to engender restoration, attachment to place, and even encourage spontaneous interaction with passersby.

The experience of touching and hearing water can reduce stress and provide a powerful connection to place and community.

The first step in identifying opportunities for integrating a Non-Visual Connection with Nature is to assess what qualities currently exist in or near your space. As the designer, what features do you have control over and which systems do you have the capacity to modify? In some cases, the intervention may be to educate occupants of the benefits of making greater use of the operable windows, whereas in other cases, the intervention may consist of programmed features that require collaboration with a mechanical engineer, acoustician, or horticulturist. The opportunities for a multi-sensory experience are endless and can be catered to the needs and programming of any environment. In all cases, consider that the non-visual connection is meant to enhance the user experience — to instill a sense of wonder, indulge positive memory, and even influence perceptions of movement or time. It’s placement should be deliberate — whether to reinvigorate without heavily distracting from the task at hand, or to encourage relaxation by stopping to smell the roses.

Filed under:

Catie Ryan

Catie is the Director of Projects at Terrapin and a leader in biophilic design movement. With a background in urban green infrastructure, Catie's interest lies in systems thinking to address human health and sustainability challenges at each scale of the built environment.

Topics

- Environmental Values

- Speaking

- LEED

- Terrapin Team

- Phoebe

- Community Development

- Greenbuild

- Technology

- Biophilic Design Interactive

- Catie Ryan

- Spanish

- Hebrew

- French

- Portuguese

- Publications

- Occupant Comfort

- Materials Science

- Conference

- Psychoacoustics

- Education

- Workshop

- Mass Timber

- Transit

- Carbon Strategy

- connection with natural materials

- interior design

- inspirational hero

- biophilia

- economics of biophilia

- Sustainability

- wood

- case studies

- Systems Integration

- Biophilic Design

- Commercial

- Net Zero

- Resorts & Hospitality

- Energy Utilization

- Water Management

- Corporations and Institutions

- Institutional

- Ecosystem Science

- Green Guidelines

- Profitability

- Climate Resiliency

- Health & Wellbeing

- Indoor Environmental Quality

- Building Performance

- Bioinspired Innovation

- Biodiversity

- Residential

- Master Planning

- Architects and Designers

- Developers and Building Owners

- Governments and NGOs

- Urban Design

- Product Development

- Original Research

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Ecology

- Resource Management

- Sustainability Plans

- Health Care

- Carbon Neutrality